"That's a good start! Once you've met someone you never really forget them. It just takes a while for your memories to return."

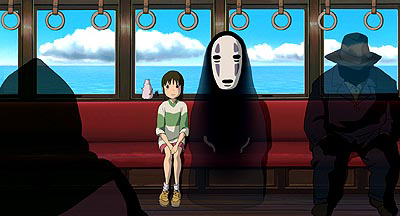

Having recently viewed Hayao Miyazaki's sprawling animated epic "Spirited Away" for the fourth or fifth time this past week, I must admit that the fantastical story of Chihiro has come to hold a special place in my cinematic heart. Beautifully executed by Miyazaki and his animation team, "Spirited Away" excels where Disney fails - it effectively creates a supernatural realm through the use of ambiguity and suggestion. Seemingly odd practices go unexplained: as the movie progresses, we slowly become attuned the conventions of an unconventional spirit world, as does our young heroine. The majesty of the spiritual realm we are unknowingly thrust into arises from its mystery. We are enamored with its variety of colorful characters and lovingly executed scenery because it is new and unexplained, instilling within us a curious child-like wonder.

Having recently viewed Hayao Miyazaki's sprawling animated epic "Spirited Away" for the fourth or fifth time this past week, I must admit that the fantastical story of Chihiro has come to hold a special place in my cinematic heart. Beautifully executed by Miyazaki and his animation team, "Spirited Away" excels where Disney fails - it effectively creates a supernatural realm through the use of ambiguity and suggestion. Seemingly odd practices go unexplained: as the movie progresses, we slowly become attuned the conventions of an unconventional spirit world, as does our young heroine. The majesty of the spiritual realm we are unknowingly thrust into arises from its mystery. We are enamored with its variety of colorful characters and lovingly executed scenery because it is new and unexplained, instilling within us a curious child-like wonder.In viewing parts of the film in its native Japanese language, I must say I have gained a new respect for "Spirited Away" - it is indeed astounding how even a superb English dubbing can dilute the content of a film. The scene in which Yubaba threatens to tear Haku to shreds after ceding to him that Chihiro may leave the bath house after a final test came as a revelation to me: I had seen this film several times beforehand, and yet this singular display of Haku's selflessness (as displayed in the Japanese version) made me rethink the entire ending of the film. It lent a new gravitas to Haku's characterization, the purity of his love for Chihiro, and his willingness to put his own survival on the backburner as he attended to ensuring her safety.

What a gorgeous sentiment... let's see Walt try and beat that one.

The final scene of the film is also best viewed with the Japanese audio, as the English translation does not do justice to the original's poignancy. The silence that marks the end of the film is a testament to the ethereal, translucent quality of the film... we are not certain of whether Chihiro has retained her memories of the spirit world, and perhaps it was a wise decision on Miyazaki's part to leave his audience with this sentiment. In all honesty, Chihiro's ability to recall her experience is irrelevant - she will remain irrevocably changed in either scenario.

All in all, this film is a homerun for parents, children, students of film, spirits, witches, toads, and all other-worldly creatures.

Simply put, this film summons an experience long forgotten by most of us - a realm in which the extraordinary is a daily occurrence, where we are the masters of our own fate. Amen.